Paediatric Orthopaedics is a specialist service which provides surgical and non-surgical treatment for conditions affecting children.

Common paediatric conditions

1. In-toe walking

2. Flat foot

3. Perthes' disease

4. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) in babies

5. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) in older children

6. Clubfoot

In-toe walking

What is in-toe walking?

Most adults walk with their toes pointing forward or slightly outward. Some children (and a few adults) walk with their toes pointing in: they have an in-toe(ing) walking pattern or gait.

Parents of children who in-toe often report that their children fall over more frequently than expected.

What are the causes of in-toe walking?

Two thirds of children that in-toe have an inwards twist to the top of their femur (thigh bone) at the hip. This is called femoral anteversion.Some children may have an inwards twist to their tibia (shin bone). This is called internal tibial torsion.In some children in-toe walking may be due to the shape their feet which are curved and tend to hook inwards. This is called metatarsus adductus.

Femoral Anteversion

We are all born with an inward twist in the femur below the hip joint. Most of us grow out of this by the age of two years.Some children take longer and tend to walk with their knees and feet turned inwards. They often like to sit with their legs in the 'W' position. In the vast majority of these children, this twist in the bone gradually disappears by the age of 7-8 years.Treatment with splints, plasters or braces does not affect it, but the doctor may advise you to discourage your child from sitting in the 'W' position.

In a very few children, femoral anteversion persists in the long-term. It is never a functional problem, however, and they can participate in sports or other physical activities without problems. In extremely rare cases of teenagers who have a severe twist that causes pain at the hips or knees, an operation may be considered to correct it.

Internal Tibial Torsion

In-toe walking can often be caused by an inward twist of the tibia (shin bone). This is very common in babies and toddlers and is due to 'moulding' of the baby during pregnancy.It may persist for a few years but gradually disappears as the child grows. Treatment with splints, plasters or braces does not alter it and is unnecessary.Tibial torsion does not cause any functional problems and children can participate in all physical activities without suffering any long-term problems.

Metatarsus Adductus

In-toe walking can sometimes be seen in children who have feet that are curved inwards (pigeon toes). This can also be due to 'moulding' during pregnancy. It is often seen in children who tend to sleep face down.More than 80 percent of children grow out of this by the age of 3-4 years.If the foot is supple and flexible (the doctor will check that) treatment is not necessary. In some children with more pronounced problems and feet that are less flexible, the doctor may recommend special shoes, splints to be worn at night or, rarely, treatment with plaster casts.Very few children need an operation for their feet to be straightened. The vast majority of children with metatarsus adductus do not complain of any symptoms, can participate in all physical activities and have no long-term problems.

Flat foot

What is a flat foot?

The sole of the foot has an arch on the inner side (instep) that extends from the heel to the base of the big toe. The foot is called flat when it does not have this arch.

What is the cause of flat feet in children?

Many people have a long-standing belief that flat feet are abnormal and require treatment with special shoes, insoles or even splints or braces.We now know that the majority of children between 1-5 years of age have flat feet. This is part of normal development of their feet and over 95 percent of children grow out of their flat feet and develop a normal arch. The other 5 percent continue to have flat feet, but only a small number will ever have a problem. Most children with a persistent flat foot participate in physical activities, including competitive sports, and experience no pain or other symptoms.Very rarely, there can be an underlying problem. The doctor examining the child will check for these and plan ongoing care. Older children with painful or stiff flat feet and children who had initially normal arches and develop flat feet later require particular attention.

Is any treatment required?

Studies involving large numbers of children have shown that treatment with special shoes, insoles or splints does not alter the shape of the foot and does not give them an arch.

The great majority of children under the age of five with a flat foot develop an arch in time without the use of insoles. Some children wear their shoes unevenly. Occasionally a small shoe insert may help - it will not alter the shape of the foot but may reduce shoe wear.

When flat feet persist in children after the age of five years and they complain of pain in their feet, treatment with insoles / arch supports is used more often to alleviate discomfort.In rare cases, young teenagers with persisting symptoms may require surgery. Children who are found to have additional problems causing their flat feet may also require an operation.

What is the outcome?

Flat feet are part of normal development in the vast majority of young children and have no long-term implications. Treatment (insoles or surgery) of older children with persistently painful flat feet has good results in approximately 90 percent of cases. The outcome for children with underlying problems depends on the condition causing flat feet.

Perthes Disease

What is Perthes' disease?

Perthes' disease is a condition affecting the hip joint in children. It is rare (1 in 9,000 children are affected) and we do not clearly understand why it occurs.

Part or all of the femoral head (top of the thigh bone: the ball part of the ball-and-socket hip joint) loses its blood supply and may become misshapen. This may lead to arthritis of the hip in later years.

What are the symptoms?

Children with Perthes' disease usually complain of pain in the groin, the thigh or the knee - particularly after physical activity. They limp and have a restricted range of movement (stiffness) of the hip joint. These symptoms may persist on and off for many months. The disease itself lasts for a few years.

What treatment is required?

About 60 percent of children with Perthes' disease recover without any treatment. It is important, however, for all children to be carefully followed up by their doctor during the course of the disease. They usually have to attend clinic every 3-4 months for examination and X-rays. In that way, children that are at risk of doing less well are identified and treated accordingly.

Treatment for Perthes' disease depends on the severity of the disease and may include physiotherapy, crutches, plasters or, sometimes, an operation to re-shape the bone around the hip joint.Parents may be asked to try to limit their child's physical activities and particularly contact sports when the disease is active.

When considering treatment, the doctor may often recommend a procedure called anarthrogram. This involves injecting dye that shows-up on X-ray into the hip joint under an anaesthetic. X-rays are then taken with the dye in the joint and these help us to decide if an operation would help.

What are the long-term effects of Perthes' disease?

These depend on how severely the shape of the hip joint is altered by the disease. Some patients will end up with painful arthritis at some stage in adult life and may require a hip replacement. In a small number of severely affected children, the symptoms of pain and stiffness persist for years even though the disease is no longer active. These children may require additional operations in childhood.More than half of the children with Perthes' disease return to normal activities within a few years from the beginning of the disease.

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

What is Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH)?

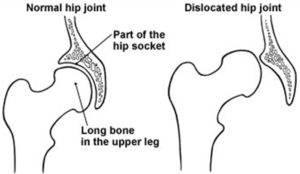

DDH is a condition where the ball and socket hip joint fails to develop normally. It can occur before birth or in the first months of life. The socket of the hip joint (acetabulum) is usually shallow and the ball (femoral head - top of the thigh bone) can be loose or completely dislocated instead of fitting snugly into the socket (the severity of the condition varies).

About 20 in every 1,000 children are born with a hip which is not stable at birth. This means that the hip may displace slightly or completely from its socket. All children in this country have their hips checked at birth, at six weeks, eight months and at two years.

Untreated, DDH may lead to pain in the hip (usually during teenage years) and the development of osteoarthritis (wear and tear arthritis) in adult life. It is therefore important to detect the condition and treat it accordingly.

Testing the hips

While all children have their hips examined, some children need the additional investigation of an ultrasound test. If a baby's hip is felt to be unstable it should be checked within 2-3 weeks by an ultrasound. Within the first 2-3 weeks most babies' hips stabilise spontaneously without the need for treatment. In a few, however, the hip stays unstable and the socket may form imperfectly. Under these circumstances children need treatment.

We know that some factors make it more likely for a baby to have an unstable hip:

1. If another family member had hip problems in infancy

2. If the baby is born by breech

3. If there are other problems in the lower limbs.

These babies should be investigated by ultrasound when they are a few weeks old.

Treatment

Splintage may be recommended when a baby's hips fail to stabilise or when the socket is very shallow. This usually takes the form of a Pavlic harness: this keeps the baby's hips and knees flexed upwards and outwards which encourages the hips to develop more normally. The harness is usually worn for a minimum of six weeks but sometimes a longer period is necessary to allow the hip to become stable.

Follow-up

Where a baby is found to have a hip which is abnormal, it is very important to follow development carefully.

For the first three or four months assessment is by clinical examination and by ultrasound, but after this period X-rays may be more reliable in judging development. When a harness is used, the babies need to be seen and reviewed for at least two years to make sure the hip continues to grow safely.

Possible problems

Some babies have hips that are dislocated and will not go back into the socket. The Pavlic harness may fail to allow these hips to go back into place properly and under these circumstances it is usual to wait until the baby is a few months old before commencing treatment.There is a small risk that even when a harness is used, and the hip reduces satisfactorily, that it will not prove enough to allow the hip to develop normally. Occasionally, therefore, such babies do need an operation when they are a little older to improve the shape of the socket.Finally, there is a very small risk that the use of a splint may interfere with the blood supply to the ball of the hip joint. This may lead to some problems with growth and development of the hip and such babies need to be reviewed very carefully in case any further treatment becomes necessary.

The outcome

Although we have outlined some possible problems, it is important to remember that the great majority of children with an unstable hip at birth grow and develop normally and do not develop early arthritis

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip In Older Childres

What is Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH)?

DDH is a condition where the ball and socket hip joint fails to develop normally. It can occur before birth or in the first months of life. The socket of the hip joint (acetabulum) is usually shallow and the ball (femoral head - top of the thigh bone) can be loose or completely dislocated instead of fitting snugly into the socket (the severity of the condition varies).

Although screening programmes allow us to detect most babies with unstable or abnormal hips, some children have an abnormality which simply cannot be detected with clinical examination and the hip may fail to develop normally.

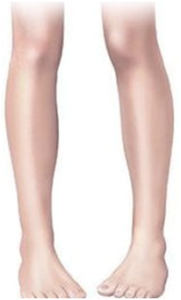

Typically when the hip displaces a little or completely, the baby's leg lies with thigh creases which do not line up perfectly and with the affected leg looking slightly shorter and rolled out sideways. Examination of the hip may show that the hip will not bend out as fully sideways or move as freely as the other hip. Sometimes both hips can be involved.

Management. When a General Practitioner, Health Visitor or Paediatricianrecognises these problems in an older child (after the age of 10-12 months) it is important to take an X-ray so that the degree of displacement can be seen and judged.

Treatment

It is sometimes possible in a child of four or five months for the hip to reduce - i.e. for the ball to go back into the socket - without any other additional treatment being necessary. Under these circumstances it is entirely reasonable to see whether a period in a Pavlic harness (a harness that keeps the baby's hips and knees bent upwards and outwards) allows the hip to stabilise more safely in the joint and allows the socket to grow more satisfactorily around the ball of the hip joint.

If the hip will not reduce, or if the Pavlic harness does not allow the hip to grow properly, other treatment is necessary. For children under the age of two years most surgeons arrange for admission into hospital for a period of preliminary traction. This means gently pulling on the leg to relax the muscles etc.

After a period of such traction it is usual to examine the baby's hips under a general anaesthetic. Often in association with this anaesthetic an arthrogram is performed. In this test a small amount of dye that shows up on X-ray is injected into the hip joint while the baby is asleep, and X-rays are taken to see if it is possible to put the ball back into the socket safely and completely. If, after traction, it is possible to put the hip back in joint in this way, the baby is placed in a plaster hip spica cast which extends from the waist down to the knees or feet. Plasters such as this always need to be changed after six weeks or sometimes earlier, under a general anaesthetic. Great care needs to be taken in looking after them!

The duration that children need to be in plaster varies. It is likely to be at least three months and may be significantly longer if it takes a long time for the hip to grow properly. Often when the plaster is removed a period of more flexible splintage may be used to keep the hip in a safe position. The great majority of babies tolerate these plasters or splints well, and immobilisation does not upset them.

Sometimes the child is walking or older still when the problem is recognised. A delay in diagnosis is likely to be greater if both hips are affected because any limp is less striking when both hips are displaced. Once children start to walk the likelihood of a successful closed reduction (i.e. putting the hip into the joint without an operation) becomes less. For children after walking age there is a significant likelihood that a surgical operation is necessary to put the ball properly back into the socket. Often there are small obstructions inside the socket which prevent the ball from falling into place properly. An open reduction will remove these obstacles to reduction and often lengthen some of the tendons that feel tight about the hip joint. Once again a period in a plaster cast after operation is necessary and once again it is likely that at least three months in plaster are required.

It sometimes happens that children are noticed with a hip problem for the first time when they are over 2-3 years old. Sometimes in older children preliminary traction does not seem to be so effective and it is often necessary when an open reduction of the hip is performed to shorten and untwist the thigh bone a little to make reduction safer and more straightforward. Once again a period in a plaster cast after the operation is likely to be necessary.

Follow-up

Whenever children are treated for a hip problem it is essential that they be kept under long-term outpatient review. Initial treatment (plaster or surgery) aims at relocating the femoral head in the socket of the hip joint. The ball and socket are not always entirely normal in shape, however, and further development of the hip relies on the capacity of the body to remodel (reshape) the hip joint after it has been relocated. Most children, particularly the younger ones respond well to this challenge. Some do not, and may need additional operations to reshape the socket or the top of the thigh bone. Secondary procedures are therefore sometimes necessary if the hip fails to develop as well as one would wish. X-rays are usually necessary for following-up hip development. We arrange to take X-rays which deliver a much smaller dose of irradiation than a normal one. This is much safer.

In general, the older the child when the diagnosis of developmental dysplasia of the hip is made, the more difficult treatment is, and the more unpredictable the results of treatment. In other words it is best if the problem is recognised in infancy and worst if it is recognised in a child over three years old. In older children the ball of the hip joint is no longer properly spherical, and the socket is no longer round, and although when the hip is put in the right place improvement can be expected with time, matching of the two slightly uneven shapes may not be perfect and may lead to early wear and tear in adult life.

Clubfoot

What is clubfoot?

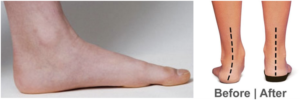

Clubfoot or CTEV (Congenital TalipesEquinovarus) is a common condition, present from the early stages of pregnancy, that causes the lower leg, ankle and foot to be twisted inwards from the normal position.

There are several theories, but the exact reason why this occurs in unknown. Boys are more commonly affected by clubfoot than girls. One or both feet may be affected.

Clubfoot can sometimes be associated with hip or spine problems, so the baby's spine and hips will be checked by the doctor or physiotherapist.

How is it treated?

We treat clubfeet using the Ponseti method, which is now the most accepted form of treatment worldwide.This is a non-surgical method that involves gentle manipulation to the foot to correct each element of the deformity. Above-knee plaster casts are used with the knee flexed to maintain the corrected foot position. We aim to begin treatment within the first week to ten days from birth; usually, weekly plaster cast changes and manipulations to the baby's foot/feet are required, in order to gradually achieve a corrected foot posture.Most babies usually require a small procedure to lengthen the normally tight achilles tendon at the back of the heel. This is normally required to gain full correction of the foot and is performed under a local anaesthetic as an outpatient; the baby will be allowed home after the procedure. A further three week period in above-knee casts will be required.

To prevent the foot deformity relapsing the baby will then be required to wear boots-on-bar. These are open-toed sandals attached to a bar, with boots set in an out-turned position. These need to be worn for three months full-time, and then at nights only until five years of age. This part of the treatment is essential for maintaining a well corrected clubfoot.

Follow-up

All babies who have a clubfoot are followed up regularly by the physiotherapy team and reviewed with the doctors every six months to yearly after treatment when the plaster casts have been completed.